We all know that Birmingham isn’t shit. We’ve spent nearly 20 years telling people, showing the world, and often undermining our case. We lay out the ineffable reasons why we say ‘Birmingham: it’s not shit’ and attempt to eff it.

We all know that Birmingham isn’t shit. We’ve spent nearly 20 years telling people, showing the world, and often undermining our case. We lay out the ineffable reasons why we say ‘Birmingham: it’s not shit’ and attempt to eff it.

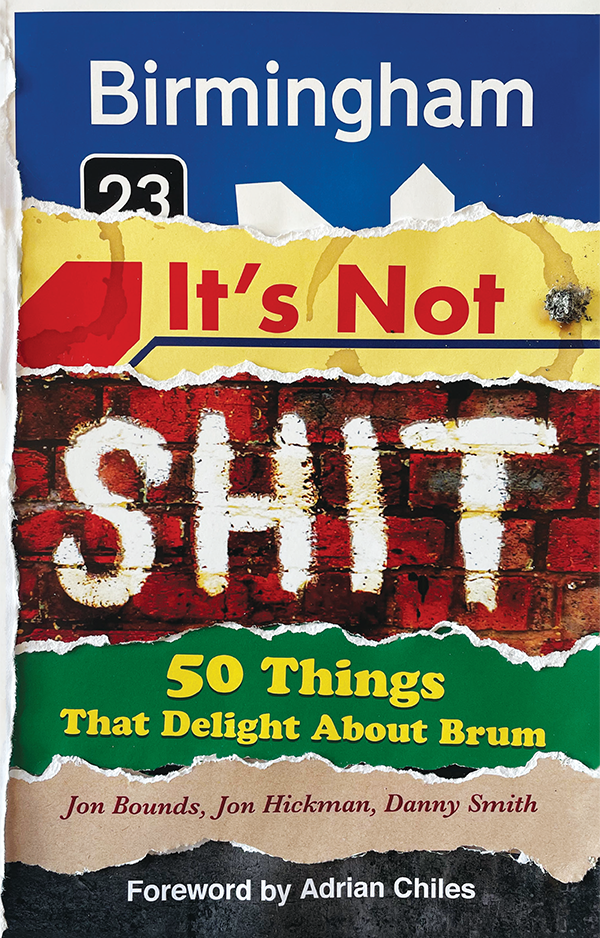

We’ve compiled 50 of the biggest things, places, people and feelings that delight us about the second city. Jon Bounds, Jon Hickman and Danny Smith will take you down Dale End and up The Ackers. If you want to find out more about Aston Villa’s sarcastic advertising hoarding, the Camp Hill Flyover, or even come with us on a journey up the M6 and find out why all of our hearts leap when we see Fort Dunlop, then come, meet us at the ramp.

Birmingham: It’s Not Shit — 50 Things That Delight About Brum

Foreword by Adrian Chiles, cover by Foka Wolf

You’re not meant to answer your phone at work, you have to do it surreptitiously. Which is why, despite Benjamin Zephaniah phoning me up to tell me just why he’d turned down an OBE in the Queen’s Christmas honours, I’m not quite sure why he did it. Phone me up, that is.

You’re not meant to answer your phone at work, you have to do it surreptitiously. Which is why, despite Benjamin Zephaniah phoning me up to tell me just why he’d turned down an OBE in the Queen’s Christmas honours, I’m not quite sure why he did it. Phone me up, that is.