Thatcher was dead: to begin with. There could be no doubt about that. Johnson had been to the funeral himself, sat near Osborne who was failing to hold back the tears. She was as dead as a doornail. Or less metaphorically, the 96 football fans who her government smeared and denied justice after Hillsborough.

It was a cold afternoon in early December, and after cancelling another interview, Johnson was heading home for an evening with a good Russian vodka given to him by a close friend. The knocker on the door of Johnson’s temporary accommodation seemed to form a face, the digits 1 and 0 became a winking eye and a nose that seemed to follow the average wage down a graph. And was what was once a letterbox a handbag?

“Boris Johnson” a modulated voice, lowered by media training.

“Yes, mummy?” he gulped.

“Mr Prime Minister sir?” Johnson shook his head. It was a police officer speaking, a short female one that he often saw beside the door.

“We’ve been collecting, Sir”

“I… I… I… er”

“For some of our colleagues down the station, those with families, Sir, some are struggling. Using foodbanks. We’re just passing the hat around, trying to give them a good Christmas.”

“I… I… I… don’t have my wallet, you know. I’ll get you on the way out.”

He went through the door that was opened for him, and snapped to an aide: “get that woman off number 10 detail.”

Stamping up the stairway he glanced at the portraits. None of them looked at him, or did the one in the pearls look as he moved past? He smoothed his hair down and pushed into his flat – it was empty, the current girlfriend and the dog thankfully absent again.

Settling down in one of the armchairs by the TV, he turned it on – flicking through the Sky box for one of those big American series he felt he had to watch in case he was asked about them in press conferences. The gangster ones were alright, actually,

He briefly rested on a BBC Four documentary, that brown portrait swirl backing of an 80s talking head. It was her, she was speaking about the miners strike. He flicked onward, leaving her in the top corner of the guide.

“Boris Johnson,” she said. But when this was recorded she wouldn’t have known him, he was still at Oxford, great days with Dave, Nick and the chaps. “Listen to me.”

He checked his glass like one of the comedy drunk tramps in a film who witness an alien landing. Surely it wasn’t spiked, damn Russians. He pressed the button and thankfully Game of Thrones came on.

“Johnson,” the voice from behind him now. “You are to be visited by three ghosts.

“Piffle,” he said. “This is a trick. Is that you Govey?”

“I am as real as I ever was,” she said. He turned and saw Margaret Thatcher. Almost as he remembered. But around her neck instead of the usual pearls was a rusting chain, pulling her down and stretching across the floor and out of sight.

“You are to be visited by three spirits.”

“I’ve barely had a drop.” he smirked, this would get the apparition on side.

“Shut up. Every word is agony, you must listen for once. Around my neck is my chain, every evil deed you do in life adds a link. It weighs around you in death, for eternity. Mine has more than three million links, for each of the unemployed and more still for the thousands of children of miners left in dead towns without hope. Your chain grows link-by-link day-by-day.”

“This is some fantasy island stuff. Did I have a bad meal? That oven-ready thing tasted a bit off.”

“Three spirits will visit you this very night. They will show you the error of your ways. They will question you and make you question yourself — or you will end up like me. Or Reagan, you should see the length of his chain.”

He stamped out of the room and shouted at his smart speaker to play The Clash. London’s Burning kicked it a high volume. The vision was to be banished.

“I decline to be interviewed by these three ghosts,” he muttered, “It’s not what the public want. Too combative, my points won’t be heard.”

When he felt the ghost was clear he moved back to the TV and wing-backed armchair and a glass of red wine. He half-watched the TV, half worked on a chapter of his new book about how the past was good. The past, mmmm. He dozed.

“Did you spill red wine on the fucking laptop?”

“Wha- I… I…”

But it wasn’t an angry blonde woman in a flowery dress. It was a man in a wheelchair. He propelled himself forward into Johnson’s shins.

“I am the ghost of Christmas Past. It’s a living, or rather not… I lost my PIP payments. I couldn’t get universal credit because some bastard spilled a drink on my laptop. The library was closed when I went to use the internet. I got nothing for six weeks. I starved. I’m dead, you know.”

“I… I’m sorry to hear that.”

“You fucking voted for it. You’ve responsible. Look out of the window.”

In the dark, stretching far past the railings at the end of the street, larger than the last anti-Trump march, were thousands and thousands of people.

“Who are they? There’s no protest authorised.”

“130,000 — all those that Tory austerity killed. Some hadn’t been able to work, some worked all hours but still couldn’t afford to eat. They are all working now, on links for your chain. Unless you change your ways.”

“I… er. I’ve only been in power around 100 days, we’re going to invest in social care, we have a plan. My record speaks for itself.”

With that the ghost of Christmas past wheeled himself out of the door and down the stairs, with a crash. Johnson put on a Gary Barlow CD and started to get ready for bed.

Just as he undid his belt and let his heavy trousers fall to the floor he noticed a knock at the door. It was the duty officer of the cabinet office.

“Prime Minister, you have a meeting.”

“This wasn’t diarised.”

“Never the less it is in your diary, and the gentleman is here. I’ve shown him in to your private study.”

The officer opened the door to the study, and Johnson, still buckling his belt held out his other hand to the tall greying man standing in there.

“Prime Minister Boris Johnson,” the introduction surely wasn’t necessary, “Professor Philip Alston, United Nations special rapporteur on extreme poverty.”

“Can I call you Philip, Phil, Pip?”

“You can call me the ghost of Christmas present.”

Johnson sighed. This was tiresome. They’d already had someone skim and dismiss this man’s report. It had been dealt with.

“You sir, are responsible for a systematic immiseration of a significant part of the British population”.

Belt now re-fastened he launched into the script. He was good at remembering lines. Not as good as Gove, Gove always had a line, but he could hold his own.

“Your report — into the previous government, I might say – was a completely inaccurate picture of our approach to tackling poverty. Great Britain is among the happiest countries in the world.

“Again, a total denial of a set of uncontested facts. In your country today 14 million people are living in relative poverty. I think breaking rocks has some similarity to the 35 hours of job search required per week to receive universal credit for people who have been out of work for months or years,” he said. “They have to go through the motions but it is completely useless. That seems to me to be very similar to the approach in the old-style workhouse. The underlying mentality is that we are going to make the place sufficiently unpleasant that you really won’t want to be here. A hostile environment, if you will.”

“If you don’t leave, this will be a hostile environment, for, er… you. I have a dog here, er… somewhere… you may have seen the pictures.”

Professor Alston looked at the floor. How could you deal with this. He walked out, straight through the door but still managed to slam it.

The Prime Minister shrugged. It was finally time for bed.

Johnson woke as the clock struck three. A little disorientated. There was a figure at the end of his bed, that of a five or six year-old child. He didn’t recognise her, but that didn’t mean it wasn’t one of his.

“I am the third and last spirt you will see tonight. I am the ghost of Christmas yet to be.”

Unexpected children turning up was one of Johnson’s great fears but he pulled himself together and sat up.

“And what do you want?”

The child looked cold, a thin coat over a dirty nightdress. Bare feet. Her voice trembled as she spoke, “I wish to tell you about my future, so that you may alter it and yours. The future isn’t written. But if you don’t change, and you don’t lose the election, I will freeze to death on the street this very Christmas eve, made homeless by your policies, left to perish by your callous cuts.”

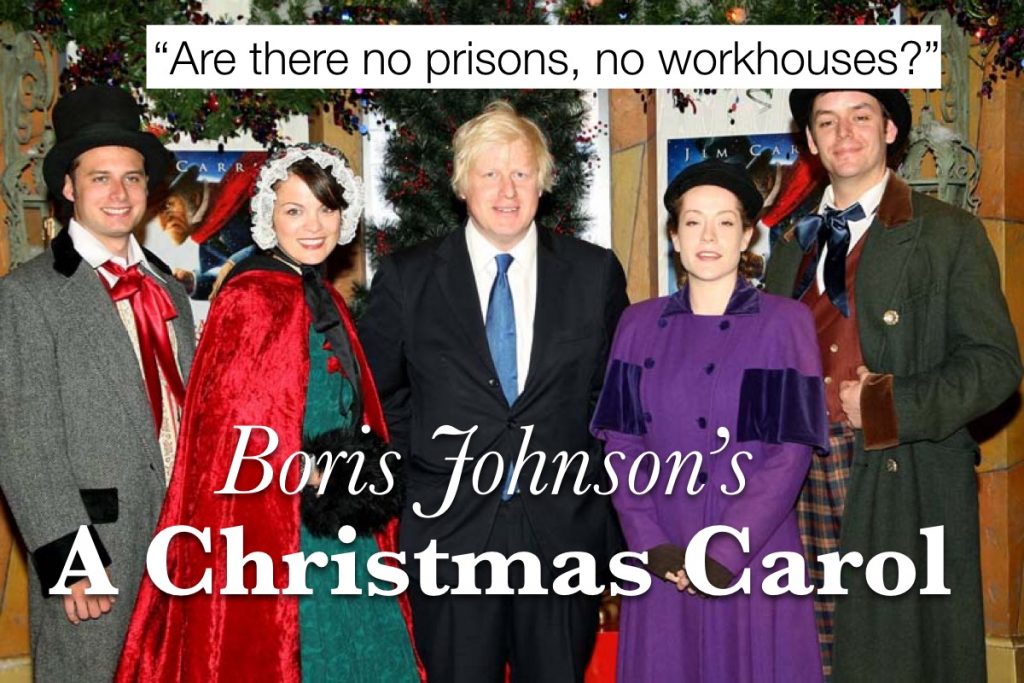

“Why are you homeless, are there no prisons, no workhouses?”

“Your rules will say my parents made themselves intentionally homeless, so we are entitled to no support. Not even a room at the Premier Inn, nothing strong nor stable.”

“This is terrible. We are going to do something.”

“To stop your chain growing Boris Johnson all you have to do is change. Something simple would do — you don’t have to stop there being billionaires, just making them pay their fair share of tax would produce enough money to house every one of the 135,000 kids who will be homeless this Christmas.”

“Er… blu…bla… I… er… we…”

He thought hard, there was no answer to this. Johnson was stumped, this was far worse than Phillip and Holly. He ruffled his hair and pointed joshingly at the freeing figure before him: “No, no this is the politics of envy. We’re going to move forward, get Brexit done. Unleash Britain’s potential”

“Of course it won’t benefit those that voted for it, but hey ho – creates more market access to the country’s public services. We’ve all gotta make a crust. Would you like to take a selfie before you go?”

The small child shrugged, pulled her coat around her and faded through wall and out into the gathering sleet.

“Dom,” he What’sApped, “take a shinny penny from party funds Go find the biggest dead cat you can. I think there are some things we need to hide right now.”

And with that, Johnson added another 17 million links to his chain.

There’s no changing them. The only good end to this story is to vote for real change and to get them out on Thursday 12 December.