Yesterday I was happy to play

For a penny or two a song

Till a fellah in a black sedan

Took a shine to my one-man-band

He said, “We got plans for you, you’d never dream”

You’re a Star, Carl Wayne’s theme song for Birmingham-based television talent show New Faces, tells the story of art constrained by commerce, of authentic culture packaged by a star system. The narrator finds success of a sort, measured in his new possessions and receives acclaim from all around but his song is a confidence trick. The only positive emotion he has is in the first line, and is already linked to the past: “Yesterday I was happy to play”.

Musically too this is dour stuff, its leaden rhythm is hidden by a sing-along hook in the chorus. This is a cathartic song. Such melancholia makes You’re a Star a strange anthem for a show like New Faces that fetishises stardom, a show whose very MacGuffin is the pursuit of fame. Yet this is perhaps the greatest trick of stardom, that it hides its shame in plain sight. Indeed New Faces‘ great rival, Opportunity Knocks, achieved much the same feat of doublethink with Kiki Dee’s Star, which camouflages the lines “They can build you up / And they can break you down / With just the right words” behind the jauntiness in an almost Smithsian way.

Now you’ll be forgiven for thinking I’m about to claim that Birmingham invented Saturday night television (it played a hand in that, of course). Possibly you suspect I’m going to say that New Faces, filmed firstly at the ATV Centre off Broad Street and then latterly at the Birmingham Hippodrome, was the first television talent show and therefore the precursor of the blockbuster global formats X-Factor, Pop Idol and, er, Fame Academy. Sadly not: Opportunity Knocks predates New Faces by many years.

Perhaps you think I will make the case for Birmingham inventing the light entertainment public vote, which is so ubiquitous in the modern talent show era? To be honest we bodged that one. The theatre audience at New Faces could vote live via push buttons wired to Marti Caine’s ‘Spaghetti Junction’ scoreboard but the rest of us at home had to write in on a postcard to place our vote. Uncle Bob and his Opportunity Knocks lot responded to the postcard innovation with a telephone vote meaning that the London show could give results on the night while here in Birmingham we had to wait a week for the postal votes to be collated. In any case, these are all petty side issues compared to the real issue at hand: how Birmingham invented the whole sham that is fame itself.

I like to think of You’re a Star and Star as folk tales, passed down among celebrities, to remind them of their place in the world, and to remind them of what needs to be done to escape their fates. These songs are also a warning to the rest of us about the true nature of fame and they have their root in Birmingham. It’s no accident then that it was Birmingham that transmitted Carl Wayne’s message to the world. For the city keeps reaching out to the world to tell it the terrible truth of fame, its hollow promises, its lies and the dreams that it likes to shatter. Witness for example Birmingham’s Walk of Stars.

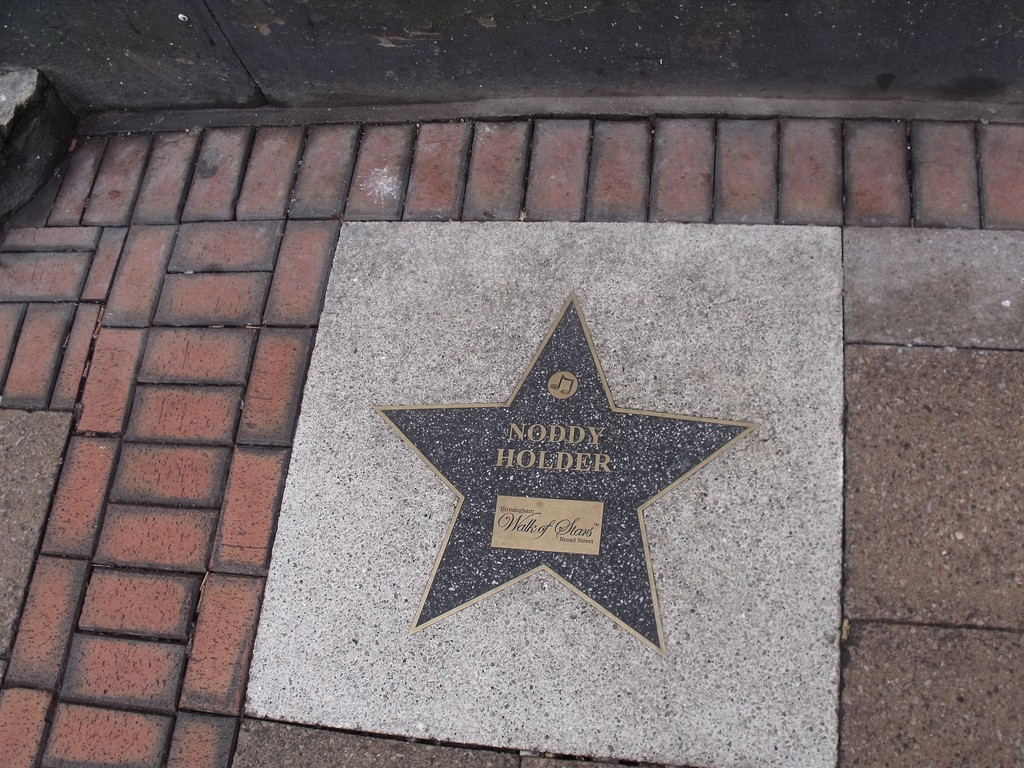

On paper the Walk of Stars is a celebration of the city’s favourite sons and daughters, a testament to their talent and their art and to the city that bore them. In reality it’s a rather dispiriting list of \middle-of-the-road\ crowd pleasers – and a lot of them are actually from the Black Country. That’s a slight exaggeration perhaps. It’s great to see Joan Armatrading there, taking her rightful place alongside Beverly Knight. Malkit Singh is there and he is a truly global star (he’s the biggest selling bhangra artist of all time) so perhaps David Bintley (the dancer, you’ve seen him) is too? The relatively recent induction of David Harewood seems a touch previous and to my eyes cynically timed: his sudden beatification happened during his supporting run on hit US drama Homeland (spoilers: his character is dead now) and doesn’t seem to connect with his wider body of work which includes being the advertising face of London. The rest of the gang are your standard Brummie household names, many of whom have now retired to play golf in Coleshill and really I can’t stress enough how many of them are from the Black Country.

The Walk is at the bottom of Broad Street, Birmingham’s party street, the crappest part of the crappest street we have in town and a location where you can often hear people ask “Is that a new star? Or did someone stumble out of the Walkabout and throw up?”. Is this glamour? No. But it is fame. It is stardom. Success in entertainment is being at the gloomy end of a shabby road lit up by gaudy lights and covered in sick (your own, someone else’s, they can’t dust for vomit). It’s greasy takeaways, a skinful of booze, and too many bad drugs. Broad Street is absolutely the right place to put this thing if you want to expose the lie of fame. That is what Birmingham is doing, systematically.

A starker reminder yet of the hollow sham of fame comes in King’s Heath where the locals decided upon their own parochial monument to stardom. The Kings Heath Walk of Fame commissioned just one star, for Toyah Wilcox, on the pavement outside of the former Ritz Ballroom. That star had to be dug up when the Ritz (by then reimagined as a Cash Converters), where the Beatles had once played, burned down — presumably to make room for another mixed-use development of flats and shops.

All of these interventions — the star walks and the folk songs — are there to remind us of a truth that was revealed long ago, with a story that starts, of course, in Birmingham.

You see stardom, super-stardom even, comes from the early years of Hollywood. Cinema audiences began to recognise certain actors as they appeared from one film to the next and then began to actively seek out more movies with the same actors. Studios responded to this by promoting the popular actors, giving them better, and bigger roles, and packaging them up for that now-starstruck audience. Narratives about the actors, about their lives, their loves, their hopes and dreams, became an important part of this packaging, this manufacturing of the actor as a star-commodity.

This all worked pretty well for the film studios until four big stars realised that they didn’t actually need those studios to run the business for them, because they themselves were the business. This Gang of Four quit their studios to form their own company. Of course they wouldn’t have been stars at all but for their creation by the same machine that they had set themselves against, but nonetheless it created a powerful story that the value in films lay with the artists, not the moneymen (in modern parlance this is known as ‘doing a Radiohead’). Those four artists were Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, and name director D. W. Griffith. The studio they created to represent their creative work was called United Artists, and within it they would have creative control over their own work (and a heck of a lot more profit).

The formation of United Artists revealed the dirty secret of the star system for the first time. Stardom was supposed to link to glamour and riches, obtaining fame was supposed to reify the American Dream, and yet here four of the fame’s most privileged scions were recasting themselves as mere labour, as indentured (but well paid) servants.

Oh, and by the way it turns out that one of those artists was from Birmingham.

Charlie Chaplin had always claimed to be from London but over the past few years evidence has come to light that places his birth “on the ‘Black Patch’ near Birmingham”. Chaplin, it’s been claimed, may have been tightly managing his backstory, creating the perfect myth he needed to construct himself as a star, changing the parts that didn’t suit. And he did become the perfect star, and with his United Artists colleagues he created a new form of stardom, a more empowered star with executive control. We can draw a direct line from Birmingham via Chaplin to Tom Cruise, who took on the running of United Artists himself in 2006. In Cruise, as with Chaplin, we have a bankable star very much in control of his own narrative, astute at managing perceptions and crucially in control of the money as well as being the public face of the work.

But we should remember that the star-capitalist, the actor who is also the owner of the means of movie production, is a rare beast indeed and for every Cruise or Chaplin there are hundreds of worker-actors, and for each of those there are thousands still whose dreams are trampled entirely. This is the world that Chaplin and the United Artists revealed to us. The worker-stars sing to themselves about this world in their folk songs, subversive messages to one another, warnings about the machinery of their fame. That’s what Carl Wayne was doing each week on New Faces — reminding us of the truth that Chaplin had revealed.

Yesterday I was happy to play

For a penny or two a song

Till a fellah in a black sedan

Took a shine to my one-man-band

He said, “We got plans for you, you’d never dream”

And of course that ‘Black Patch’ wasn’t even in Birmingham and it turns out that Chaplin was actually from the Black Country. It’s just another lie, another piece of empty myth-making but it all fits. Let’s get Charlie a star on Broad Street, just outside the Walkabout.

Photo CC: Elliot Brown